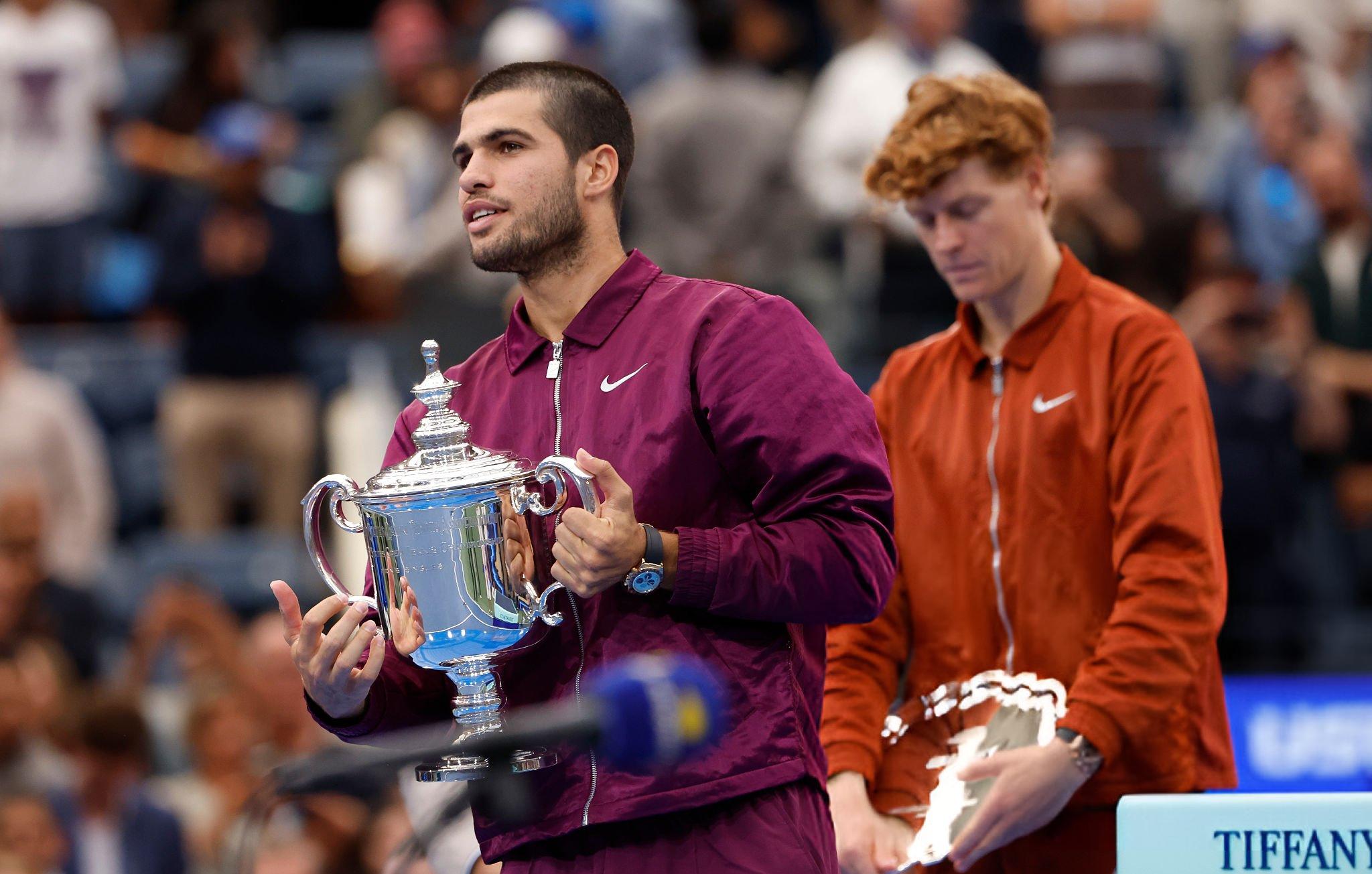

After an uncompromising duel at "Roland Garros," it seemed the new meeting between Carlos Alcaraz and Jannik Sinner would once again set the tennis world ablaze. But the US Open title match turned one-sided: Alcaraz won 6:2, 3:6, 6:1, 6:4, and the feeling of a "Grand Slam" masterpiece never materialized. The main reason was Sinner’s far-from-ideal performance; he couldn’t handle the pace, the pressure, or his own expectations.

Alcaraz Gets It Done: Serve, Discipline, Textbook Hitting

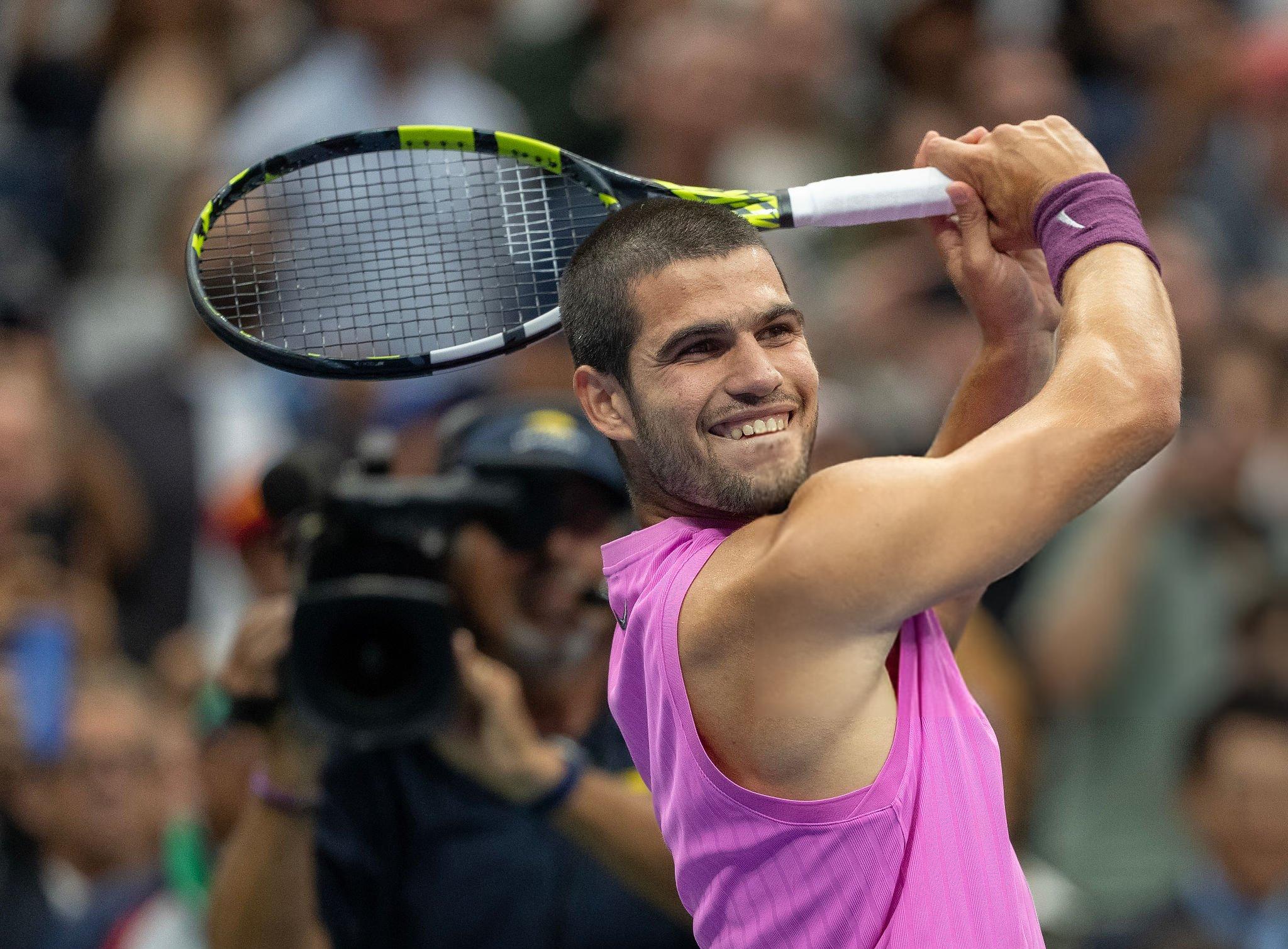

The Spaniard played an exemplary tournament with the first serve — across seven matches he was broken only three times, and the final merely confirmed the progress. In key moments Carlos consistently found a heavy first ball: in the fourth set at 15:30 on his serve, when Sinner was desperately hunting a break back, he fired two aces in the next three points — and the tension immediately eased.

Alcaraz’s plan was thoroughly pragmatic: put the serve in with quality, return deep, and then smother the opponent with the forehand, directional changes, and foot speed. He seasoned it with flair — sparingly: slices to draw the opponent into the court, well-timed drop shots followed by lobs and passing shots. Crucially, the creativity never turned into recklessness: throughout the match Carlos didn’t hit a single poor drop shot, and risk was almost always supported by position.

Sinner's Meltdown: Percentages, Tempo, Concentration

The Italian, by contrast, played perhaps his worst match in two seasons. The first thing that stood out was the collapse in first-serve percentage (about 48%). For a Grand Slam final that’s almost a verdict: without free points and first-strike dominance, Jannik was forced into longer exchanges where Alcaraz is faster, more adaptable, and more varied.

For Sinner it’s vital to keep the tempo high and not let Carlos open up — otherwise the Spaniard lays out the rally step by step and reaches the ball in an ideal hitting position. In the final that tempo kept breaking down for Jannik: at times he was steady, but more often — too sluggish and predictable. Under pressure Sinner looked unexpectedly helpless: forehands flew long after good first serves, double faults crept in at 30:30 and 40:40, and the backhand “switched off” when he tried to hold serve. In total he was broken four times and donated numerous points less to the opponent’s brilliance than to his own sloppiness.

Physical or Psychological?

An easy explanation suggests itself: in the semifinal the Italian called the trainer because of abdominal issues and assured he would be fine by the final. Even if the discomfort hadn’t fully gone, a touch of reduced freshness against Alcaraz flips the match. But the mental side also failed: either an excess of emotion — or, conversely, not enough fire — led to late starts to the ball, hesitant decisions near the lines, and delayed adjustments on return. As a result, Jannik either played in “get-through” mode or fell into strings of unforced errors, with the score running away quickly.

A Single Bright Stretch — The Second Set

There was a brief period when Sinner found his rhythm: he took the second set thanks to earlier contact on return, forehand-to-forehand aggression along the diagonal, and better court positioning after the second serve. But that window didn’t become a trend. Early in the third, Alcaraz regained control with depth and direction, Sinner’s first-serve percentage dipped again, his accuracy on big points wavered — and the match fell back under the Spaniard’s dictate.

What's Next: Adjustments Without Which There Will Be No Title

The roadmap for Sinner is clear and grounded. First, stabilize the first serve: adding miles per hour isn’t essential; improving the percentage and varying locations matters more — that way he opens the court more often with the first strike. Second, restore tempo on return: a step inside the baseline against the second serve, an aggressive reply down the middle to rob Alcaraz of time. Third, on the big points, simplify choices: less fine artistry from awkward positions, more reliable geometry to higher-margin targets.

In New York Alcaraz showed he can win finals without fireworks — through discipline, depth, and error-free execution of the obvious. Sinner proved the opposite: when the first serve dips and concentration frays, even his outstanding ball-striking turns into a string of risky attempts. The US Open final wasn’t a classic not because the players’ potentials are unequal, but because only one of them truly played that night. For their duels to return to epic status, Jannik first needs to stop losing to himself.