The latest round in the top leagues produced a whole scattering of strange, at times almost anecdotal episodes, behind which very rational tactical decisions are hiding. Some coaches are using free weeks without European competition to turn set pieces into their main resource. Others leave their superstars on the bench to restore order at the back. Some essentially grant themselves a timeout via a goalkeeper's “injury”, while others keep banging their heads against the ceiling of positional attacking development. Let's see how these details add up to a bigger picture.

When the Schedule Helps: United Power Up Their Set Pieces

Manchester United dragged themselves back from 1–0 down at home against Crystal Palace to win 2–1 – both goals came from set pieces. Ruben Amorim's team already have ten goals from dead-ball situations, as many as table-toppers Arsenal and Chelsea.

The Portuguese coach does not put it down to luck alone. United have no European fixtures, and the coaching staff are basically living on the training pitch, drilling blocks, rehearsed routines and movement patterns in the box. In the Premier League you cannot survive without this – opponents are constantly searching for micro-advantages, and Ruben admits openly that some ideas were simply “borrowed” and adapted.

At the other pole is Crystal Palace. Oliver Glasner once again complained after the match about how hard it is for his team to play immediately after a Conference League game: zero wins, one draw and three defeats in such rounds. The meeting with United was a textbook example: the first half belonged to an energetic, aggressive Palace, the second half to a drop in intensity which the hosts exploited, squeezing the visitors with set pieces and superior depth.

Salah in the Shadows but the Defense in Order: Slot's Experiment

Liverpool snapped a three-game losing streak, calmly dismantling West Ham 2–0 away. Arne Slot's side allowed the opponent to create only around 0.3 expected goals – one of the Reds' best defensive performances of the season.

The key decision was Mohamed Salah starting the game on the bench while the entire right flank was reshaped. Joe Gomez came in at right-back, with Dominik Szoboszlai working ahead of him and, in this structure, operating almost like a wing-back: joining in attacks but tracking diligently back when possession was lost.

The main objective was to take Malick Diouf, West Ham's best distributor from left-back, out of the game. The Gomez–Szoboszlai pair played the full 90 without being substituted, and the outcome speaks for itself: Diouf did not complete a single progressive pass, only the second time that has happened all season.

The contrast with the previous Liverpool is obvious. With Salah on the right flank, opponents were increasingly punishing the team via their own left-backs: four assists from that zone, more than from any other position. Now the bet on balance and discipline has clearly paid off.

A Tactical Theatre Break: Donnarumma and Guardiola's Timeout

The match between Manchester City and Leeds turned into a full-on emotional rollercoaster. The hosts were cruising at 2–0, but after the break Daniel Farke switched his side from 4-3-3 to 3-5-2, refreshed the flanks with substitutions – and the game flipped on its head. City could not keep up with Leeds' new structure, their pressing collapsed, counterattacks poured in and the score became 2–2.

At the peak of the chaos, Gianluigi Donnarumma suddenly grabbed his leg and went down on the turf. The referee had to call on the medical staff, and Pep Guardiola used the pause to gather all his outfield players around him – effectively creating a full-blown timeout that does not officially exist in football.

After the game Farke did not hide his anger: he called the episode an act of cynicism and admitted that the referees are practically powerless to do anything about it. Pep, for his part, did little to disguise the fact that he used the break to rebuild the pressing structure that had fallen apart following his own earlier tweaks.

The impact was partial. Leeds did manage to equalise, but after that City regained control. Following the penalty incident, the visitors mustered only a single shot on goal.

There is another important point: this kind of trick is nothing new for Donnarumma. At PSG he staged similar “pauses”, for example in the second leg of the Champions League semi-final against Arsenal, when the Parisians used them to disrupt the rhythm of Thomas Partey's long throw-ins. It remains anyone's guess who floats the idea more often – the goalkeeper himself, sensing that the team is sinking, or the coaching staff.

The Ceiling of Ideas: Tottenham's Positional Attacks Under Frank

By the seventh minute at home, Tottenham were already 2–0 down against Fulham and eventually lost 2–1. For Thomas Frank's side it turned into the perfect test of their positional attacking quality: the visitors sensibly dropped into a deep block and handed over the ball with barely any objection.

Instead of a siege and a deluge of chances, though, what emerged was a dull cardiogram. The passing map of the match highlights an almost obsessive idea: in prolonged attacks the ball is funnelled again and again to Mohammed Kudus on the right flank. There is a “one-and-a-half” variation when Xavi Simons comes on, but the principle does not change.

In such one-dimensional conditions, Spurs produced only 0.57 xG from open play – catastrophically low for a team that had nothing to lose from the opening minutes and simply had to take risks.

Frank is now getting hammered by criticism, and not without reason, but it is important not to forget the huge body of work he did as the coach of underdog Brentford. The difference in the job description is enormous: there, opponents rarely stress-tested his ideas about positional play; here, they do it every week. And it is precisely in this area – the need to constantly generate new attacking solutions – that the Dane is clearly struggling.

Diaz as the Final Chord: Bayern's New Positional Play

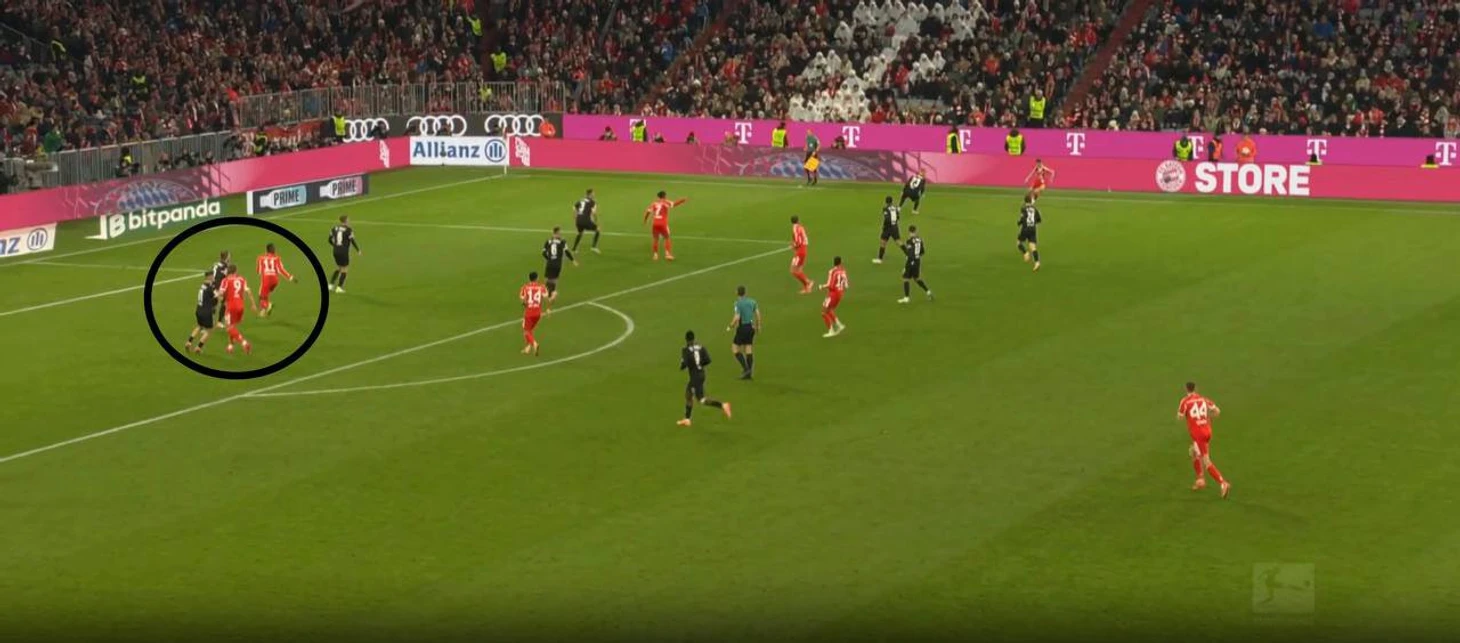

Luis Diaz has slotted into Bayern so naturally that it feels as if he has spent his entire career in Munich. The match against St. Pauli once again underlined that impression.

The first goal starts with a typical Diaz move inside and a run onto a ball chipped in behind the centre-backs – the Colombian finds space in the half-channel and then calmly squares the ball to a teammate.

The second goal is all about his trademark finish. At the moment of the cross Diaz is not even in the crowd inside the box; he starts from deep, bursting into the gap between the lines while the defence tracks Harry Kane and Nicolas Jackson, who are locked to the middle.

In both episodes his teammates “tie up” the centre-backs – they have to mark their men rather than read the passing lane – and Diaz exploits the space opening up from deep. Bayern have long had enough players capable of creating such corridors, but they lacked that one “tarzan” to swing through the vines and arrive in the decisive zone. Now that missing piece finally seems to have been found.

The Bundesliga's Delicate Surgeon: Leon Avdullahu

Another revelation is Hoffenheim's playmaking midfielder Leon Avdullahu. In one of his signature episodes he uses what does not even look like his strongest left foot to slice a pass through the space between the opponent's defence and midfield lines. The ball travels along the ground with perfectly calibrated pace: once it pierces the pressing block it seems to slow down by itself, leaving his teammate with a simple task – control it and carry the attack on.

For Avdullahu, moments like this have become a weekly serial. Almost every pass he plays that breaks lines yet is easy to bring under control is a small aesthetic delight for tactics aficionados. He is only 21, and Hoffenheim paid Basel just eight million euros for him. For a Bundesliga that adores creative central midfielders, this is a potential star for years to come.

Catching Long Throws with Your Hands? Rulli Tests the Theory in a Real Match

Many fans have an intuitive question: why do goalkeepers almost never charge out aggressively for an opponent's long throw-in and try to claim the ball with their hands?

Geronimo Rulli of Marseille decided not to leave the idea at the theoretical stage and tried exactly that in a 2–2 draw against Toulouse. He was meeting long throw-ins not on the edge of his six-yard box but almost in the middle of the penalty area.

The outcome of the three key episodes was as follows:

- 1. He came out into a challenge, misjudged the flight, but a teammate collected the second ball.

- 2. He came out again and this time earned a foul in his favour.

- 3. He got stuck in no man's land and conceded.

The problem is that a ball from a throw-in often follows a “parachute” trajectory and frequently lands further from the byline than a corner does. The goalkeeper has to run further, track the ball in the air for longer and at the same time read the players' movements. Even the slightest delay can leave him either trapped in the middle of the crowd or stranded in between, confusing his own defence.

It is no surprise that while the idea looks attractive in theory, it almost never gains traction in practice. It is obvious that many coaches have tried this approach in training and, judging by how rarely we see such episodes in games, have decided that it is simply too risky an experiment.

Conte's Napoli: The Right Wingers for a 3–4–3 System

Antonio Conte's Napoli have found their rhythm: three wins in a row, thanks in no small part to the switch to a 3-4-3 shape and a change in the profile of the wide players. In all the games since the break the Italian has trusted a front three of Lang, Hojlund and Neres.

The 1–0 victory over Roma, just like the win against Atalanta a week earlier, was delivered by David Neres. Once again Conte went all-in, removing one of Napoli's most useful players, Matteo Politano, in favour of the Brazilian.

Politano is a classic sticky dribbler who constantly demands the ball to feet, squeezes the space around him and tries to cut through the defence with a string of take-ons or short passes. His movements thicken the game up and make it heavier.

Neres offers more variety and fits the new structure better. Politano looks for the ball in order to reach a dangerous zone with it, while David looks for space in order to receive the ball there (even though he can also play in Politano's style). After moving to a 3-4-3, Conte did not start winning straight away because the wing profiles did not match the new conditions. By backing the Brazilian, he has found the chemistry between the second wave and the new centre-forward.

Neres scored against Roma by darting in behind when Hojlund held up the ball on the flank – in that situation Politano would almost certainly have moved closer to Rasmus, deciding that he needed support. With similar runs, David also shredded Atalanta's back line.

Runs In Behind by Catalan Design: Barca's Refreshed Attack

Raphinha's first start in two months immediately made Barcelona's attacking play more varied. His runs in behind produced the first two goals. First the Brazilian found space in the box for a low cutback and cross – after a slight deflection the goal was officially credited to Robert Lewandowski – and then he unbalanced Jonny Castro and accelerated onto a chipped ball over the top.

These were not the only examples. In another episode Raphinha popped up on the right and exploited the extra attention being paid to Lamine Yamal.

Nor were the movements coming only from Raphinha. Dani Olmo was constantly searching for gaps in Alaves' back line, dragging their holding midfielder out of the centre and back with him, and at half-time Marcus Rashford came on – another forward who loves to run in behind.

Yet even with this set of players it still feels as if Barcelona are not squeezing everything out of these vertical runs. Throughout the match there were moments when the movement of Raphinha, Olmo and Rashford went unanswered in favour of a safer option on the ball.

A World Where Details Decide Everything

Put all of these stories together and a clear trend emerges: the fate of matches is being decided less and less by abstract notions like “character” or “motivation”, and more and more by very concrete details – from how much time a team can devote to set pieces to how willing a coach is to sacrifice a star's status for the sake of discipline on the flank.

A fake injury that turns into a timeout, a bold but controversial experiment by a goalkeeper on long throw-ins, a complete change in wing profiles for a new system, a bet on a young playmaker who can slice through lines – all of these are bricks in the same process. In the top leagues there is virtually no room left for banality: every micro-move is carefully thought through, and the line between a brilliant idea and a disaster lies in a handful of tiny details.