Charles Barkley is a rare example of a sports megastar whose charisma and self-irony outlasted both his career peak and the absence of a championship ring. A legendary 1990s power forward, the 1993 MVP and a Basketball Hall of Famer, he has long been one of the NBA’s voices on television and a symbol of perpetual good humor. But behind the smile and jokes lurked a weakness that “Sir Charles” for years called a habit: gambling. By his own admission and media tallies, his total losses in casinos reached roughly $25 million — the price of a war against the house in which the outcome is almost always foregone.

Las Vegas's Generous "Santa Claus"

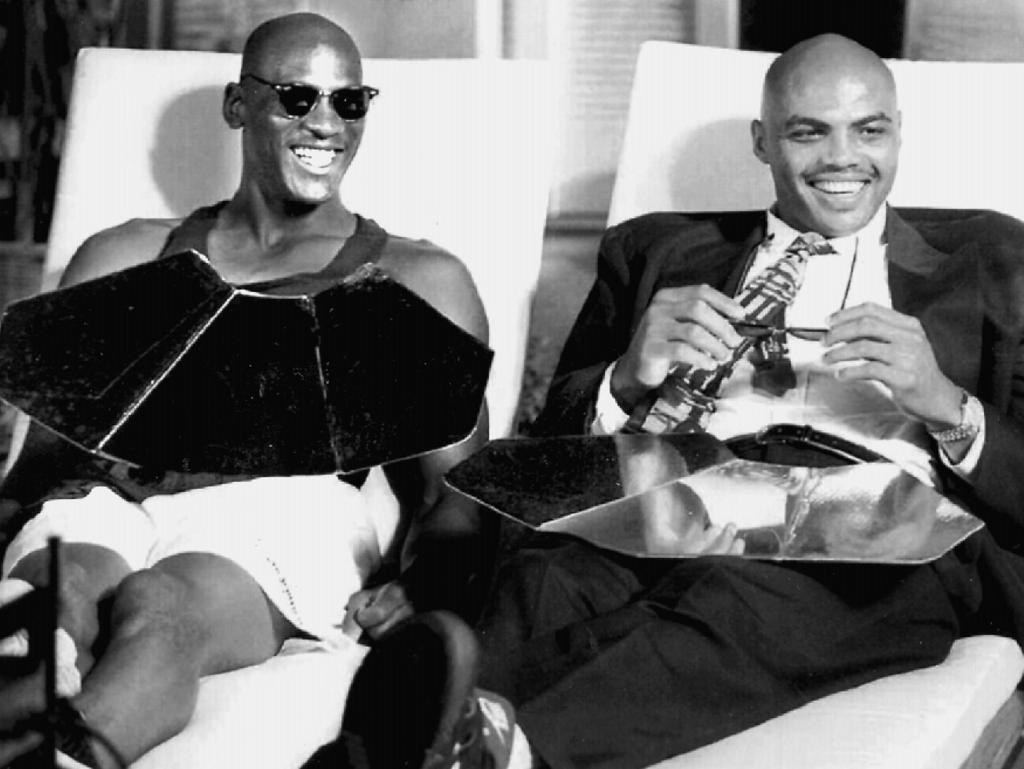

In Las Vegas, Barkley was not just a VIP guest — he was adored as a benefactor. He would casually leave paycheck-sized tips, slip hundreds of dollars into a janitor’s or server’s pocket, and once bought fifty bottles of tequila to hand out like Halloween candy. Casino staff would swap shifts just to work the night Chuck was in town: to them he wasn’t a problem gambler but a walking celebration. Even friendly ribbing from the likes of Michael Jordan — don’t throw cash around — slowed him only briefly. Generosity was part of the persona and, it seems, a way to justify an endless hunt for a big score.

An Obsessive Benchmark: "Taking" a Million in a Weekend

Every trip to Vegas started with the same goal: win a million per visit. Not a particular game or strategy — the seven-figure mark itself became a fixation. Local chroniclers like Norm Clarke remember Barkley as a magnet for crowds: the table with Chuck turned into a stage, and any night became a show. The problem is, shows rarely end on time. Friends begged him to stop when he was up $300–$400 thousand and just enjoy the night, but Chuck dug in: until the counter hit the coveted million, the night wasn’t over.

Blackjack in the Company of Legends

Stories of high-stakes nights with Barkley have long since become urban lore. One vivid episode — a blackjack session with Michael Jordan, former world No. 1 Pete Sampras, and Mario Lemieux; Chuck also roped in Mark Cuban, who at the time was not yet the owner of the Dallas Mavericks. Cuban approached the table with “modest” hundreds while chips worth five and ten thousand per hand were flying around. Charles set the level of play — the tempo, the atmosphere, the dose of risk. But time and again the same dynamic led to one outcome: the marathon toward a million turned into laps in the desert.

Roller-Coaster Highs and a Bid to "Tame" the Stakes

On his best nights Barkley could be up $600–$700 thousand, but when the gauge neared a million a breaking point usually kicked in. At some point his friends persuaded him to change tactics: instead of going all-in, cap the bankroll at a few hundred thousand so a weekend’s result wouldn’t dictate the mood for the week ahead. Chuck admitted it: winning a million feels fantastic, but losing the same amount sinks you into a funk. Keeping it in a half-million window made defeats tolerable and wins still sweet. Even so, that “safety net” didn’t always save him from a cascade of emotion-driven decisions.

It's Not the Casino — It's Me

Barkley spent years describing his relationship with gambling as a “bad habit you can control.” He emphasized that he didn’t see himself as clinically addicted — he simply liked to play for big money because he could. Yet the sober admission echoed in every interview: you can’t beat the house; in the long run the casino takes its share. At his most candid he did the math himself: once he won $5 million in a single night, about seven times he won $1 million, but roughly twenty-five times he lost $1 million. The ledger speaks louder than any responsible-gaming slogan.

A Two-Year Pause and Jokes Through Gritted Teeth

After a string of painful defeats Barkley really did take a break — nearly two years. When he returned to the tables he would joke on air: “I’m not planning to die with this money — otherwise my family will fight over it while I’m burning in hell.” But the jokes didn’t change the facts. When hosts advised him to “stay away from roulette,” Chuck would smile — and still admit it was he himself who kept walking into the same trap. A close friend put it more bluntly and to the point: the issue isn’t gambling; it’s that Charles stubbornly chooses a losing game against math and his own temperament.

The Loudest Falls: Six Hours, Minus $2.5 Million, and a Lawsuit from Wynn

Barkley’s chronicle of defeats has precise dates. In 2006 he lost $2.5 million in just six hours — a reminder of how fast even a very large bankroll burns at high limits. In 2008 came a lawsuit from Wynn Las Vegas over an unpaid gambling marker (about $400 thousand wagered on the Super Bowl). The matter reached the threat of criminal prosecution, and only after the story became public did Barkley pay the debt and around $40 thousand in court costs. He then publicly vowed to “quit.” As with many a gambler’s promise, “quit” meant more a change in tone and a temporary pause than a final break.

An Outcome You Can't Beat With a Bet

Barkley remained a social phenomenon: at the table he wasn’t just buying cards and chips — he was buying attention, the staff’s respect, the smiles of chance acquaintances, the illusion of total control over the evening. In basketball his strength and talent faced opponents — and for decades he could answer them on equal terms. In the casino his opponent was the house itself and its statistical edge. You don’t argue with that defense: it doesn’t tire, it doesn’t lose focus, and over the long run it always squeezes you.

Charles Barkley is still one of the league’s most vibrant and honest voices — a man who laughs at himself louder than at anyone else. Perhaps that honesty is what makes his gambling story instructive. He didn’t hide the falls, didn’t bury the numbers, didn’t shift the blame. He simply tried for far too long to beat math with charisma. And math — like championship banners — can’t be bluffed.