Wayne Rooney's career had everything: Manchester United and England national team records, trophies, and the status of a generational icon. But behind the glittering facade were years when he numbed his anxiety with alcohol and lived on the edge. Today Rooney speaks about this openly — about how he could drink for two days straight and then score on Saturday, only to relapse again; about the anger that pushed him toward heroics and mistakes; and about the person who, by his own admission, kept him alive — his wife, Coleen.

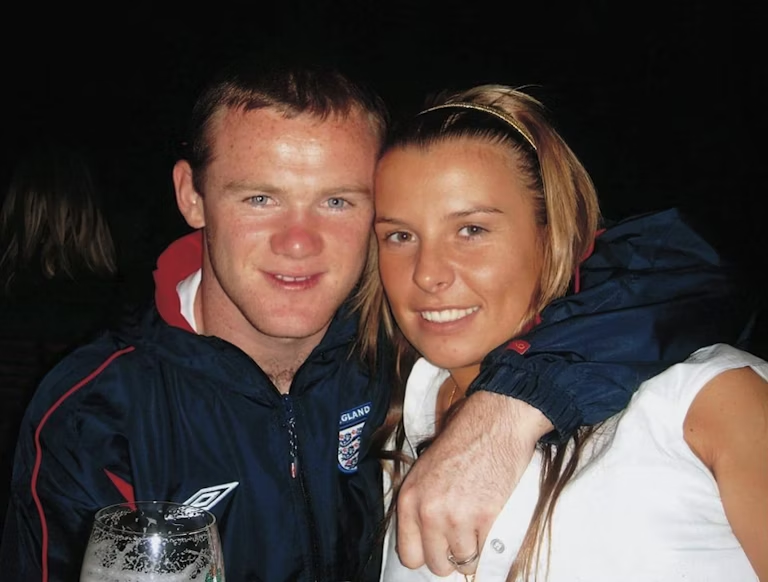

“Two Kids From Croxteth”: A Family Backline That Never Fails

Their story began long before fame. Two kids from Liverpool’s Croxteth — Wayne and Coleen — walked the road together from school dates to their 2008 wedding. The couple have four sons: Kai Wayne (2009), Klay Anthony (2013), Kit Joseph (2016), and Cass Mac (2018). Rooney is blunt: Coleen acted as his “external manager,” noticing when he was losing control, drawing boundaries, and pulling him back to reality. “If it weren’t for her, I wouldn’t be alive today,” he says now; it isn’t a pose — for more than twenty years she kept him from steps he could never fully repay.

Alcohol as an “Anesthetic” to Pressure: What Hid Behind the Smiles in Photos

Rooney’s rise was dizzying: at 16 he scored his Premier League debut goal against Arsenal, after Euro 2004 came global stardom and a move to Manchester United. Media scrutiny, fans’ expectations, managers’ demands — the pressure was such that he searched for an “off switch.” That switch became alcohol. He would shut himself off from the world to “switch off his head,” then return to the training ground in the morning, masking the traces of a sleepless night with eye drops and chewing gum. The Saturday whistle worked like a timer: score — and it felt like control was yours. In reality, it was an illusion of control and a spiral that lasted several years.

Peak Football at the Edge of a Cliff: Why It's So Dangerous

The paradox of those years is that a significant portion of Rooney’s “golden” spell at Manchester United coincided with the storm inside. He was winning the Premier League and the Champions League, piling up goals — which made it easier to fool himself: if I’m fine on the pitch, everything must be under control. In truth, the bill came later — when pace and sharpness no longer covered the damage, body and mind collected what they were owed. Rooney says that both the culture he grew up in (“you don’t talk about feelings”) and the fear of “burdening” his loved ones made it harder to admit the problem openly.

Anger as Fuel: When Emotions Make You Stronger — and More Vulnerable

The second axis of his confession is anger. Childhood prickliness and sporting aggression were long part of the “Rooney brand”: he surged forward, fought for every duel, but with the charge came side effects — silly red cards among them. He recalls how, before a match against Chelsea, he once swapped the studs on his boots for longer ones — the anger was boiling so much he wanted opponents to “feel” the battle. Over time he learned to put a brake on that inner engine — and suddenly realized that a slice of the dangerous imbalance that made him so unpredictable for defenders had drained from his game. The fine line between fire and burnout is a lesson learned late.

2006 and the Carvalho–Ronaldo Case: The Conflict That Never Happened

The red card in the 2006 World Cup quarterfinal trailed Rooney for years. The tangle with Ricardo Carvalho and Cristiano Ronaldo’s look turned the scene into a meme, but Wayne stresses there was no personal war and no split at Manchester United. In the tunnel he spoke first: the media would hammer them both, but back at the club they would do their job — and they did. Even today he isn’t sure how deliberate that stamp was: the “fog” of emotion can blanket a pitch as well as London smog.

The Conversation That Changes Everything: A Path to Help and a New Regimen

The turning point began when Rooney dared to talk — not hiding the “bad days,” but calling them by name. Psychotherapy gave him tools: he learned to recognize when an internal “blast” was building and to stop himself by talking it through — with a professional or with those close to him. Coleen is still the first to spot warning signs. Rooney is careful to add: he doesn’t consider himself an “alcoholic” in the clinical sense; he can have a drink, but he now knows the price of “control” and doesn’t gamble with it. The keys are boundaries, discipline, and honesty with yourself.

Why It's Important to Talk About This: Lessons for the Industry and Young Players

Rooney’s story isn’t about weakness, but about growing up. Elite football still cultivates a code of silence: “take the hit and don’t whine.” Yet sometimes the blow lands from within — from anxiety, guilt, the weight of expectation, and the public microscope that hunts for hairline cracks in your biography. Against that backdrop, “a night out” looks like an easy exit: it’s simple, accessible, and offers temporary calm. The problem is that the next day you often try to prove — to the world and, first of all, to yourself — that everything is under control. Each such “proven” match only postpones the conversation you should have started yesterday.

For academy prospects, this should read like a handbook: find someone who can tell you “stop”; don’t be afraid to ask for help — it isn’t weakness, it’s professional hygiene; protect the source of your energy — let your emotions work for your game, not against it. For clubs, it’s another signal: psychological support in elite sport isn’t a luxury but infrastructure at the touchline; a short list of specialists matters as much as the striker depth chart.

A Period Instead of a Comma

Rooney lived through the part of a career many choose not to speak about. He doesn’t romanticize his binges or hide them behind trophy photos. He names names, owns mistakes, and credits those who pulled him back from the edge — first and foremost, Coleen. Above all, he reminds us that a footballer remains a human being: fears and lapses are part of the package, and only honesty with yourself can break the closed loop of “scored — drank — scored” and replace it with a simpler, more mature rule — “live and play.”