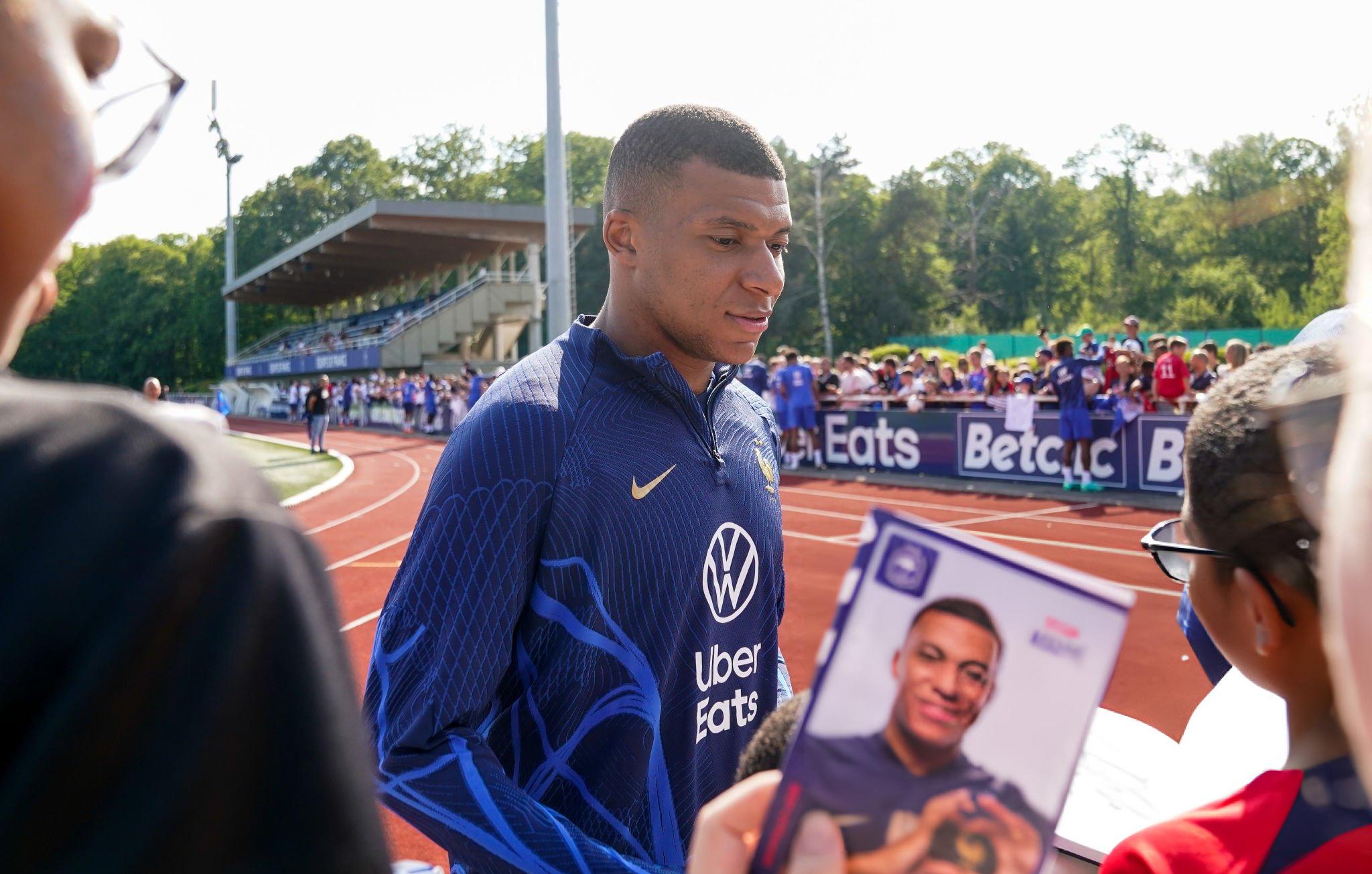

He laughs easily but speaks hard truths. His answers mix football pragmatism with a level of candor rarely seen in a global star. Jorge Valdano met with Kylian Mbappé in Madrid and talked about everything: from a brutal calendar and painful setbacks to lessons from Messi, sharing the stage with Vinícius, and that feeling when you score three in a final and still don’t lift the cup. This interview is a long-form dialogue: no blindfolds, no bowing to titles, with respect for the game and the reader.

This conversation is not a transcript. Here, Mbappé doesn’t dodge sharp angles or hide behind clichés. He calmly owns his mistakes and speaks just as calmly about his dreams. Core themes: early fame and growing up at the elite level, the sting of defeat and the taste of victory, the work of body and mind, the manager’s place in the modern game, and the difference between being a legend and walking toward legend.

The New Rhythm of Football: What an Overloaded Calendar Does to a Player

— Kylian, today almost every top club plays twice a week, the breaks are melting away. What is it like to live inside that rhythm?

— This is a different kind of football. We want to play — it’s our profession and our passion — but the density of fixtures demands adaptation. The season is no longer a “preparation–peak–taper” cycle; camps are shorter, recovery happens on the run, and you’re constantly operating at high revs.

— The year after the Club World Cup felt especially heavy: there was almost no pre-season.

— Yes, we basically moved from one tournament straight into another. It was an experience clubs and players hadn’t really prepared for. But a professional adapts. You rebuild your nutrition, sleep, and micro-recovery blocks. I fell ill during the Club World Cup — dropped about seven kilos. I put some back on and suddenly felt lightness, speed, freedom in my burst. My final weight ended up a bit lower than last year — and I feel good with it.

— “There was no pre-season — but you started by flying” is a tempting conclusion.

— What matters isn’t the start, it’s the distance. Everyone is quick in August and September. The league and the Champions League are decided in spring, and trophies are won in May. Our task isn’t a flash; it’s holding a steady line at maximum.

Metropolitano as a Cold Shower: Why Defeats Are Worth Remembering

— That derby night at the Metropolitano felt like a lesson with a loud snap to many.

— Exactly. When it’s 2–1 and you concede four more, your world flips. Atlético went into the match like a final; we went in like a routine league game. They won the intensity in duels and the second balls, and the pitch tilted. In games like that, if you’re getting beaten in the clashes, you won’t regain control. It was unpleasant but useful. You shouldn’t forget it: the right kind of memory is insurance against repetition.

2026 — Not Repeating 2022: How the Dream of a Second World Title Lives On

— You’ve scored four goals in World Cup finals. It looks like at least one more shot lies ahead.

— One is certain, and it’s not far off. And I want to win it. In 2018 we lifted the cup; in 2022 we went all the way and fell at the finish. It hurts. But football is generous with second chances. We’ve drawn our lessons.

— What does it feel like to score a hat-trick in the final and leave without the trophy?

— In a final you don’t count goals; you count the minutes to the whistle. The game was crazy, and Argentina were better over the distance. We had our strong spell, but overall they deserved it. It’s a bitterness that doesn’t wash away, but you can process it. Then you move on — toward the next World Cup.

— Spain as a challenge?

— They manage tempo and the ball beautifully; it’s a schooling that runs from the academy to the senior team. Right now, probably the best team in Europe. But the World Cup has a different tournament biology. We’ll see. And yes, I hope on the day that matters they play a little worse (laughs).

"I Knew I Wasn’t Henry or Pelé." The Sobriety of 16 and Choosing Monaco

— When did you realize that the dream of being a professional wasn’t a poster image but you?

— At Monaco, when I was 14–15. Everyone around said “special.” My parents shielded me from the noise, but in the academy I saw a system where growth wasn’t a miracle, it was an expected trajectory. The whole environment tells you, “You can.” And you start living like a professional long before your debut.

— After trials at Real you returned to France; later you chose playing time over a glamorous bench spot.

— Careers are like fingerprints — everyone’s pattern is different. I listened to my family, but the decision was mine. I wanted to play, not just be on a list. Back then Madrid’s line was Benzema — Cristiano — Bale. Not the right time for a young starter. Paris gave me seven incredible years. But I’d dreamed of Real since childhood and made the move when I felt it was mine.

— Being compared to Henry and Pelé at 16 — is that a heavy cap to wear?

— No, if you look in the mirror honestly. At 16 I was a kid who hadn’t done anything yet. Comparisons are great for newspapers, not for a training plan. I saw clearly: the path was just beginning.

"For Lamine — Passion; The Rest Will Catch Up." On Talents the World Watches

— Today Lamine Yamal stands where you stood yesterday. What would you tell him?

— Times are different, platforms are different, and so are clubs: Barça is 24/7 floodlights. There’s no universal recipe. But one thing is timeless: passion. If he keeps that, the rest follows. It’s better not to talk much about personal life — let him grow on the pitch. Eighteen is the age of mistakes. The key is to learn quickly from them.

Social Media, Mental Health, and "I’m Proud of My Mistakes"

— How do you view social media, where punches land without gloves?

— Social media is a place without a red carpet. Before you enter, understand this: it will be harsh. If you accept that — fine. If not — don’t go in. Players sign up for criticism with their contracts; it’s part of the job. The tougher part is for those who didn’t sign — families, kids, the people around you. They need protecting.

— You speak often about your own mistakes.

— Because they made me who I am. I made mistakes — and I’m proud they weren’t fatal but became my textbooks. Listen, analyze, don’t repeat — it sounds like a slogan, but it’s the only working method of growing up.

Paris, Great Teammates, and Lessons From Leo

— The first impression at PSG isn’t just big names, it’s the density of star air. How does an 18-year-old breathe in that?

— I wasn’t ready for a twist like that. But once I stepped over the line onto the pitch, every difficulty turned into pleasure. I grew up in Paris among Neymar, Dani Alves, and many others. Five seasons — top scorer? That’s a line in the stats. Far more important are the feelings you give people and the moments that stay with the team: a Champions League final, trophies, a shared history.

— Leo Messi.

— When you say “those who wrote history,” you think of him. In daily life he’s extremely normal and respectful. On the pitch — unique. Next to a player like that, a striker’s job is to open his eyes and learn: movement, first touch, pass, rhythm. Two years with him — a golden school. I’m grateful for the experience.

— Why did PSG take so long to win the Champions League?

— In football, a lot gets decided in a single window of opportunity. If you don’t use it, someone uses it against you. We had semi-finals and a final — that means we were close. Defeats like that don’t burn you; they dry your brain out: you learn, and you act differently the next time.

"In Madrid They Love You for Your Work — and Just Because." The City, Pressure, and Daily Life

— What surprised you in Spain?

— The warmth of the people. You arrive and, even before you’ve done anything for the city, you’re treated as “one of us.” Madrid respects personal space: yes, people ask for photos and autographs — that’s part of my life. But they’re tender even with my family, who don’t speak Spanish. Details like that mean a lot.

— Is the pressure at Real different from Paris?

— Pressure has been my companion since youth. The difference is elsewhere: Real is the best club in the world, and here you place extra demands on yourself. You see walls saturated with trophies and names and tell yourself: “Be an example. Help the team. Win.” That’s useful pressure — it raises your daily standard.

— The scandalization around Real — just part of the background?

— It’s not a Spanish quirk; it’s the media world. Two bright players on one team is a headline writer’s dream. But a headline isn’t a dressing room. Inside, our common goal is trophies. Noise outside is constant; the problem starts when there’s no noise at all.

"With Vinícius We Need to Be at Our Best — at the Same Time"

— There’s a lot of talk about your relationship with Vinícius.

— We get on great. More and more each month, because we understand each other better. He’s an outstanding player and a really good guy. For Real to be where it should be, both of us have to be at our peak — not in turns, together.

— You scored a World Cup final hat-trick and didn’t win. At Real you have the Golden Boot, but no trophies yet.

— Now that truly carries weight. And that’s what we’re going to change. Trophies are a collective currency. You can’t order them for delivery; you go and take them from your opponent in May.

Ancelotti and Xabi Alonso: Two Schools of the Same Victory

— What’s the difference between Carlo Ancelotti and Xabi Alonso for you?

— Two different generations, each with its own temperament and optics. Carlo is one of the greatest ever. His dressing room is a space of trust. He’s there; he knows when to hug and when to say nothing. Xabi is younger, his ambition speaks louder — naturally. It’s his first big chapter at the best club in the world. Our job is to translate his ideas into the language of victories. Ideally — immediately.

The Tactical Era: The Manager as Chief Architect

— Do you feel how football is changing?

— Very much. The game has become more tactical and methodical. The manager’s influence has grown: more and more you recognize a team by the coach’s accents. Before, individualities weighed more; now system play opens the door for more players to reach the elite. That’s good: the doorway isn’t wider, it’s fairer.

El Bicho and a Path Without Copies

— Your reference point is Cristiano Ronaldo.

— El Bicho! (smiles) For me he’s always been an example of discipline, longevity, and obsession with detail. In Madrid he’s No. 1, a legend, a shared memory that still inspires people. I’m lucky to hear advice from him. But I want to walk my own path. If one day people dream about me the way they dream about him — it will mean we took the right steps.

— At a certain checkpoint you and he had the same number of matches and goals — the kind of coincidence statistics love.

— For him it lasted nine years; for me a year and a half. The important thing isn’t arithmetic, it’s the vector: every season has to add meaning, not just numbers.

"Having an Opinion Means Earning the Right Enemies"

— Last question. In a public profession, is having your own opinion a risk?

— Yes. It creates opponents. But they’re the right kind of enemies: they appear when you defend what you believe in. You can’t be convenient for everyone. Football appreciates those who stand by their word. If one day I have a real, serious problem — not media foam — I’ll say so myself. And I want to be heard precisely then.

"The Right to Make Mistakes Is the Right to Grow": A Closing Instead of a Conclusion

This conversation easily condenses into a formula Mbappé repeats for a reason: “I’ve made a lot of mistakes — and I’m proud of that.” There’s no pose in it. It’s sports math: there is no progress without mistakes. His view of the game is adult: the calendar isn’t an excuse but a task of managing your form; the memory of pain isn’t theatrics but insurance against repetition; trophies aren’t social posts but the result of spring routine.

Even with Ronaldo’s name alongside his, Mbappé isn’t in a hurry to put on someone else’s legend costume. He dissects coincidences calmly, separates noise from substance, and returns to the basics: passion, discipline, responsibility. He recalls Monaco as the right school of maturation and speaks about Messi without trembling awe, but with the precision of a professional who knows how to watch and absorb in training. He explains that with Vinícius the mission isn’t alternating solo shows; it’s synchronizing peaks. He admits the Metropolitano was an icy shower, and the 2022 final is a scar that doesn’t fade but reminds him why he’s here.

The main takeaway is simple and stern in a way that suits sport: greatness isn’t an endless streak of perfect matches; it’s the ability to be the best version of yourself and your team on the day that matters. For that you need managerial ideas — from Ancelotti’s wisdom to Xabi’s fresh ambition — respect for the craft, and the courage not to hide your voice. And if football truly “gives you many chances to prove everything,” as Kylian says, then his next chance is already marked on the calendar — somewhere between a Madrid spring and the summer of the North American World Cup.

Will there be room in this story for one more defining match and one more cup? Words don’t write that answer; May lineups do. But listening to Mbappé, you believe: he’s understood — and he’ll make it in time.