Wimbledon is the oldest of the Grand Slam tournaments, and every detail is steeped in legend—especially the trophies presented by the All England Lawn Tennis Club on the final weekend. Why do men raise a gilded cup topped with a miniature pineapple, while women lift an ornate silver plate? We explored the story behind the symbols that have become the hallmark of the London championship.

48 Prizes in Two Weeks: The Parade of Wimbledon Trophies

Throughout the tournament the organisers hand out almost fifty trophies. Cups and plates go not only to the winners and finalists of the adult singles but also to players in doubles, junior, veteran and wheelchair events. Yet the spotlight invariably focuses on two flagship awards—the men’s Challenge Cup and the women’s Venus Rosewater Dish. These trophies are as emblematic of Wimbledon as strawberries and cream or the strict dress code on the lawns.

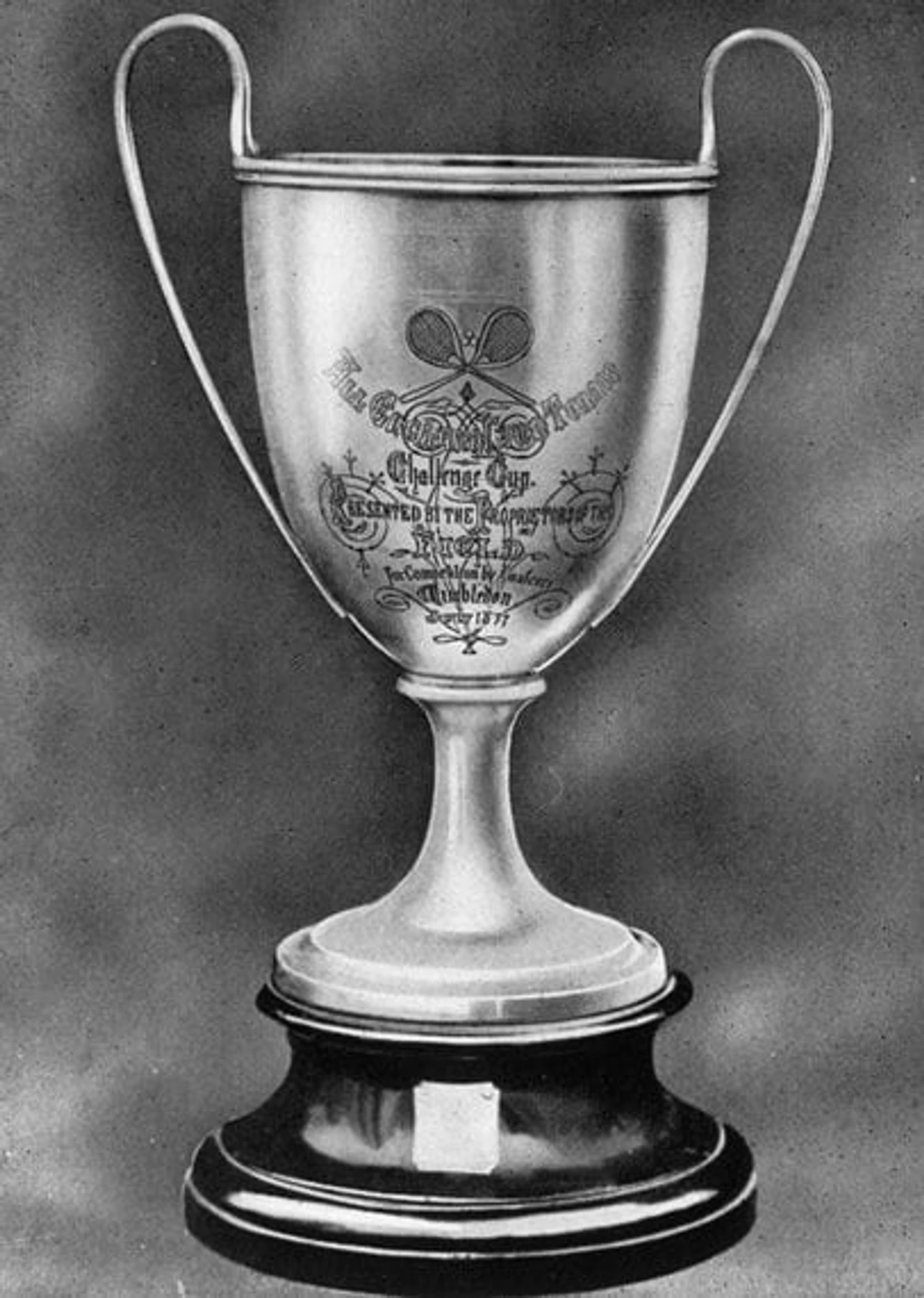

The “Golden” Cup With a Pineapple: The Birth of the Men’s Trophy

Until 1887 champions competed for the Field Cup and later the Challenge Cup, which they could keep permanently if they won the tournament three times. William Renshaw used this privilege, claiming both cups thanks to six consecutive victories. The club had to commission a new award and allocated 100 guineas—around £7,000 in today’s money, roughly a skilled craftsman’s annual salary at the time—for the 11th edition of the championships.

The new cup, 18 inches (about 46 cm) high, was made of silver thickly coated in gold. Its body bears the inscription “The All England Lawn Tennis Club Single Handed Championship of the World”. Under each handle is a relief of an antique helmet—an homage to Victorian classicism. Crowning the lid is a pineapple. According to the Wimbledon Museum, growing pineapples in 17th-century Britain was impossible: the exotic fruit was imported, gifted to monarchs and seen as a symbol of wealth. Thus the pineapple became the perfect emblem to top the gilded cup.

Until 2008 champions’ names were engraved directly on the body. When space ran out, craftsmen added a plinth. Today’s champion receives a 35-centimetre replica inscribed with the names of earlier winners, while the original is spared unnecessary travel.

The Rosewater Plate: The Metamorphosis of the Women’s Prize

The women’s singles debuted at Wimbledon in 1884, and the first champion, Maud Watson, took home an elegant silver flower basket. Two years later organisers changed course and ordered a large, partially gilded rosewater dish—18 ¾ inches in diameter—from Birmingham. In early modern England such dishes were presented to guests after a meal along with rose-scented water for rinsing fingers, a ritual described in Mark Twain’s “The Prince and the Pauper”.

The Wimbledon plate is an exact copy of a 16th-century pewter original now in the Louvre. Hence its design features an antique motif unrelated to tennis: in the centre sits Sophrosyne, the personification of moderation and prudence, long mistaken for Venus. She holds a lamp and a jug—symbols of enlightened reason and purity. Around her are figures of deities and elements, while the outer border shows Minerva presiding over the seven liberal arts—geometry, arithmetic, music, rhetoric, dialectic, astronomy and grammar. Leafy ornamentation weaves the mythology into delicate filigree.

From 1949 to 2006 champions received 20-centimetre miniature copies; since 2007 the women’s winner has taken home a reduced replica the same size as the men’s—35 cm. Names of champions up to 1957 are engraved on the front, later names on the back.

Eighteen Minutes for Eternity: The Engravers Who Write History

Every champion longs to see their name etched in precious metal as soon as possible, and that moment comes almost immediately after match point. For nearly forty years the speed and precision were the responsibility of a single man, Polish engraver Roman Zoltowski. His family’s wartime odyssey took them from occupied Poland to Siberia, the Middle East and finally Britain. Settling in Wimbledon and working for a table-silver supplier, Zoltowski became the sole craftsman the club trusted with its tennis trophies.

Zoltowski devised a method that allowed him to engrave the champion’s name in 18 minutes, while the stands were still buzzing. Each year he drove his red MG the 1,400 km from Poznań to London, taking the trophy—still bearing sweaty fingerprints—into a cramped workshop behind Centre Court. Only once did he fly, when his car broke down; airport security grew suspicious of his tools, and he never used a plane again.

In the 2010s Roman retired, and the baton passed to London firm Rebus, headed by Emmet Smith. Now a four-person team sets up a pop-up workshop under the stands, and the champion raises the freshly engraved trophy to the cameras within minutes of victory.

Why Tradition Outweighs Change

Wimbledon could long ago have standardised its prizes—giving the women’s champion a classic cup or shrinking the mythological plate into a medal. But in the club’s offices and jewellers’ workshops they understand the value of symbols. The Rosewater Dish and the pineapple-topped cup have lived side by side for nearly a century and a half, surviving world wars and the switch from wooden to graphite racquets, and they remain integral to the tournament’s identity.

Their contrasting shapes reflect the Victorian aesthetic that strictly divided “men’s” and “women’s” spheres in tennis. Even today, as sport strives for gender balance, the two distinctive trophies remind spectators of the discipline’s history—from corseted ladies mastering the sliced volley to tweed-jacketed gentlemen debating whether an overhead serve should be legal.

The Delicate Mathematics of Prestige

Every gram of precious metal in the Wimbledon trophies works for prestige. The men’s cup is silver coated with gold—the silver-gilt technique—making it easier to clean and safer to show to the public, as pure gold scratches easily. The women’s plate is also silver, but only selected reliefs are gilded to accentuate the pattern. The museum safeguards the originals: finalists receive exact replicas, while the real pieces leave only for exhibitions under insurance worth millions of pounds.

A Living Legacy

The Wimbledon trophies are more than works of art. They embody human stories, jewellers’ craft and cultural memory. When Novak Djokovic or Marketa Vondrousova lifts the cup or the plate, they become part of an unbroken chain stretching from Victorian England to future generations of tennis players. As long as the golden pineapple crowns the cup and Sophrosyne keeps watch on the silver plate, the premier tournament of the grass-court season will have tales to tell and surprises for every viewer who tunes in to Centre Court.