In today's sports world, betting brands are as much a part of the landscape as club logos and tournament crests. They are in news headlines, on players' shirts and in broadcast graphics. But the roots of this giant industry lie not in football or basketball, but in a world where the central figure is the horse. Modern betting – its odds, margins and the habit of expressing probability in numbers – was born around racecourses. And that birth had a price: a noble animal really did become an instrument of human gambling.

Modern Horse Racing: An Elite Club Drowning in Its Own Traditions

In the 21st century, horse racing lives in a strange duality. In terms of the money that flows through bets, it is still among the elite, but in terms of mainstream public interest it is in a prolonged crisis.

In the United States, where racing was the leading gambling entertainment just a century ago, dozens of tracks have closed since the early 2000s – more than forty venues have disappeared from the map. In Britain, a number of historic courses have long since given way to airports, university campuses and residential developments. The number of races has also collapsed: in 1989 more than 74,000 races were run in the US, but by the mid-2020s that figure had dropped below 31,000. In the United Kingdom, attendance at horse races fell below five million spectators per year for the first time since the mid-1990s, when data collection began – and the trend is still downward.

The reasons are obvious, and there are several of them:

- The economics are limping. Maintaining stables, paying staff, transporting horses and running racecourse infrastructure often costs more than ticket sales, sponsorship and media rights bring in. Where the business case does not add up, tracks simply close and the number of fixtures shrinks – hardly fertile ground for popularising the sport.

- It is one of the most dangerous sports of all. In statistics on fatalities among participants, horse racing is near the top. And this is not just about jockeys: from the mid-2000s to the early 2020s around seven thousand horses died on American tracks, while in Britain hundreds of thoroughbreds are lost in a single year. On Australian racecourses, on average one horse dies every few days.

- The industry struggles to communicate with the new generation. For decades marketing was aimed at a narrow audience – mostly well-off white men approaching retirement. Young fans, women and ethnic minorities, the very groups driving other sports, are barely represented in this world. To these new audiences, horse racing often looks overly complicated, formal and “not for us”.

American businessman and racehorse owner Mike Repole puts the diagnosis bluntly: racing hardly knows how to promote itself, and in the public sphere it is talked about mainly in negative terms – injuries, doping scandals and controversy. Positive stories, educational projects and youth initiatives either do not exist or look hopelessly outdated. Without a serious marketing reboot the sport risks ending up as a museum piece.

Yet behind this gloomy picture there is still a huge flow of money.

Horse Racing as the 'Sport of Kings': A Money-Making Machine

Look not at the grandstands but at the financial reports and it becomes clear that horse racing is still one of the most expensive and profitable segments of the sports industry. The estimated global value of racing and associated betting runs into hundreds of billions of dollars – more than the entire games industry and several times the worldwide box office of cinema.

Two key sources support activity on this scale.

First, racing provides a perfect setting for expensive entertainment and business networking. From the outset, horse racing was seen less as a mass sport and more as a status symbol. A race day is an occasion to put on your best suit or most extravagant hat, meet in a VIP box and discuss deals against the backdrop of the parade ring. The racecourse is often more important as a social stage than as a purely sporting facility. Contracts are agreed here, the right people meet, and everyone shows which circle they belong to.

As long as this audience has money and interest, organisers are in no hurry to radically change the format for the sake of new spectators: the feeling of a “closed club” is more valuable to them than potential mass growth.

Second, racing is one of the cornerstones of global betting culture. Despite its old-fashioned image, horse racing regularly ranks alongside football, American football, basketball and tennis in lists of the most popular sports for betting.

The average horse-racing bettor in developed countries is also far from ordinary:

- a significant share of bettors earn more than the national average income;

- most have a university degree, and many hold a master’s or doctorate;

- a large proportion see betting not only as entertainment but also as an investment tool, while simultaneously trading on the stock market.

In other words, this is not “cheap” gambling but a playground for people with resources and a feel for numbers. To understand why this audience has been drawn to racecourses for decades, we need to go back to the past, when the British aristocracy combined equine speed, a taste for risk and a habit of careful calculation.

From Chaotic Wagers to a System of Odds

Before the first professional bookmakers appeared, the British satisfied their appetite for gambling with almost anything: dice games, cards and simple lotteries. The centres of this activity were pubs, where bets were taken even on what now look like horrific blood sports – animal-baiting contests and cockfights. In London there was even an official set of rules for cockfighting, with detailed regulations and, crucially, instructions on how to accept bets.

But there was a natural ceiling to such entertainments: too much blood, too little respectability. To build a durable and reputable industry, a more “noble” object of gambling was needed – and the horse filled that role.

At first, horse races were purely utilitarian. Sellers and buyers held trial runs to test the speed and stamina of horses before sale. Chroniclers in the 12th century described the Friday horse market in the London district of Smithfield: knights and nobles came there to look at horses, assess them and, if necessary, buy them. At a given signal the riders would send their horses flat out, and the crowd would shout and argue as they watched.

It is not hard to imagine that money quickly entered the picture: at first owners and their entourages would bet with one another, and then spectators joined in. For a long time, however, these bets had no formal mechanism. People simply agreed amongst themselves on which horse to back, and the “line” was usually limited to straightforward win-or-lose wagers.

The situation began to change at the end of the 18th century.

Onto the stage stepped Harry Ogden, widely regarded as the father of classic bookmaking. He understood racing exceptionally well, could assess a horse’s chances quickly and was not afraid to risk his own money.

In the 1790s Ogden set up a small betting stand next to Newmarket racecourse and offered a radically new approach: each horse had its own odds reflecting its perceived chance of winning. For the first time, customers were given a genuine choice:

- back the favourite and aim for a smaller but more likely return; or

- side with the underdog, accept higher risk and chase a big payday.

Ogden built into these odds what we now call the margin. If he rated a horse’s chance of winning at 20%, the “fair” price would be 5.00. But to give himself a safety buffer he would quote a slightly shorter price, say 4.00 – which in percentage terms is 25%.

This is exactly the adjustment that produces the famous sum of probabilities above 100% when you convert odds into implied chances and add them up: if you turn both sides’ odds into percentages and total them, you see a few extra percentage points – that surplus is the bookmaker’s profit. The trick is not to overdo it: an overly greedy operator quickly loses customers, while one who is too generous risks emptying their own bank.

Ogden’s idea was quickly embraced by the English elite who frequented the racecourses. His successors began to write all bets and odds into special ledgers, and so the term “bookmaker” – literally, “the one who makes the book” – took root.

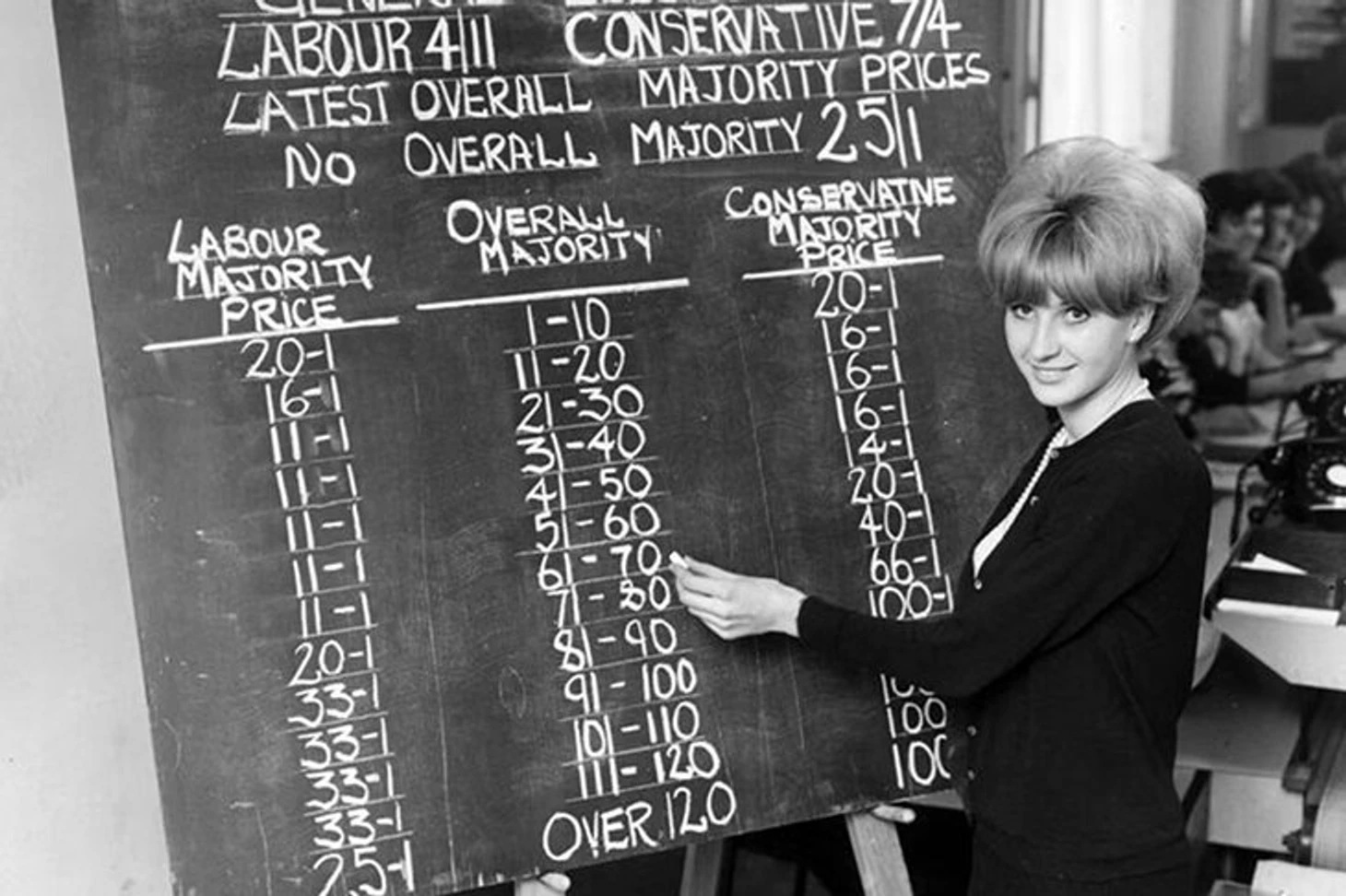

The next step was to take betting off the racecourse itself. In the mid-19th century Londoners Leviathan Davis and Fred Swindell opened one of the first betting offices where you could wager on horse races without setting foot in the stands. They also distributed sheets around the city with the odds they had set for upcoming races – a prototype of today’s betting coupons and online markets.

In this way horse racing moved beyond being a diversion for aristocrats and became the foundation of an entire sector.

Between Prestige and 'Vice': How the Aristocracy Legitimised Gambling

Even in the 19th century, as public morals grew stricter, the English continued to grant horse racing a special status. Philologist and theologian John Ashton, a fierce critic of “betting mania”, wrote that although the horse is a noble creature, it had been turned into an工具 of a vice that was corroding society from within. The very fact that his attack was directed at racing is telling: this sport was so deeply woven into elite culture that it could not simply be dismissed as something low and contemptible.

Under the patronage of monarchs and aristocrats, racing gradually acquired:

- the first major prize funds – such as the sizeable sums awarded to victorious knights in the time of Richard the Lionheart;

- courses that became institutions – like Newmarket, opened under James I and quickly established as the “heart” of British racing;

- national rules – such as those introduced by Charles II, which set the age of horses, the race distance and the format of competition;

- new centres of attraction – like Ascot, founded by Queen Anne and still one of the most elegant fixtures in the royal calendar;

- regulatory bodies such as the Jockey Club, which standardised the rules, oversaw thoroughbred breeding and worked to make racing more transparent;

- closed clubs and auction houses like Tatersalls, where wealthy owners bought and sold thoroughbreds and simultaneously backed their own horses with bets.

Even in the 20th century, the royal family remained deeply involved in racing. Queen Elizabeth II personally bred horses, the royal stables won hundreds of races, and racing was a fixed point in the monarchy’s calendar.

Memoirs and newspaper clippings from the 18th and 19th centuries are full of accounts of which lord or duke staked how much on which horse. While moralists urged that prize money be redirected to “more useful” fields such as agriculture, the upper classes continued to see betting on racing as an expensive, risky but entirely acceptable habit.

It was this top-down acceptance that helped bookmaking survive the early waves of regulation and prohibition relatively unscathed.

Bans for Workers, Freedom for All: How Laws Strengthened Bookmakers

At first it seemed that the state barely interfered in this world where the nobility themselves set the prizes and bet against each other. But as the working class was drawn deeper into the game, the patience of the authorities ran out.

Several serious problems had emerged:

- complete legal chaos – debt disputes between bookmakers and bettors clogged the courts, yet there was no legal framework to rely on;

- no taxation – income from gambling and betting flowed entirely outside the state coffers;

- moral panic – especially in the Victorian era, when betting was viewed as a sinful pastime that corrupted the soul.

The first step was the 1845 Gaming Act, which effectively declared all private wagers “unenforceable” in law: if you bet and lost, that was your problem; if you won but the bookmaker did not pay, that was also your problem. At the same time, fines and prison terms were introduced for fraud in racing.

Some bookmakers withdrew from the racecourses and moved into small offices and informal premises. But a new law in 1853 banned such betting houses as well. As you would expect, betting did not disappear – it merely became harder to monitor.

At the same time industrialisation, expanding railway networks and rising working-class incomes turned a trip to the races into an affordable and attractive day out. On major race days special trains were laid on from all over the country, and entire entertainment districts grew up around the tracks. Even a direct ban on street betting in the early 20th century failed to stop the process: bookmakers simply switched to taking bets by telephone and post, settling accounts by cheque or on credit and exploiting gaps in the law.

William Hill, now one of the giants of the industry, began life in the 1930s as exactly this kind of “remote betting” service. By the mid-20th century legislative logic had changed completely: it was recognised that keeping an ingrained habit under control was easier than waging war on it. In the 1960s gambling and betting were officially legalised in the United Kingdom, and yesterday’s underground bookmakers suddenly became respectable market players.

Meanwhile racing was conquering the world. Television broadcasts, and later the internet, turned the Kentucky Derby, Melbourne Cup and other prestigious races into globally watched shows. Thoroughbreds like Secretariat became national heroes, and their victories turned into part of countries’ cultural memory.

At the same time, racecourses faced a new kind of competition: faster, more spectacular sports like football, basketball and motor racing, as well as casino games, lotteries and online slots. Doping scandals, on-track tragedies and debates about animal welfare added to the pressure. The pace of technological progress outstripped traditional sport’s ability to adapt – and today racing is paying for that delay.

From Roman Chariots to Mobile Apps: What Horses Have Left Us

Roll history back a little further and it becomes clear that staking money on the outcome of a contest and turning a sporting event into a financial risk predates the British lords by many centuries. In ancient Rome, chariot racing was a full-fledged industry: hippodromes seating hundreds of thousands, faction teams with owners, managers and fanatical supporters, bets on winners and crashes, fixed races and the “grey” earnings of sponsors.

The Romans made gambling part of everyday culture, stripping it of its aura of sacred “divination” and recasting it as an ordinary – if still criticised – form of entertainment. Centuries later, when horse racing in the modern sense took shape in the British Isles, this attitude towards risk and wagering was already embedded in society’s mindset.

In this story the horse has travelled a long road from working animal to principal symbol of “civilised gambling”. Around it there emerged:

- the first systematic odds;

- the concept of the margin and “skewed” probabilities;

- betting offices and their lines;

- tax and legal mechanisms to regulate betting;

- the habit of seeing sport not only as a spectacle but also as a field for investment.

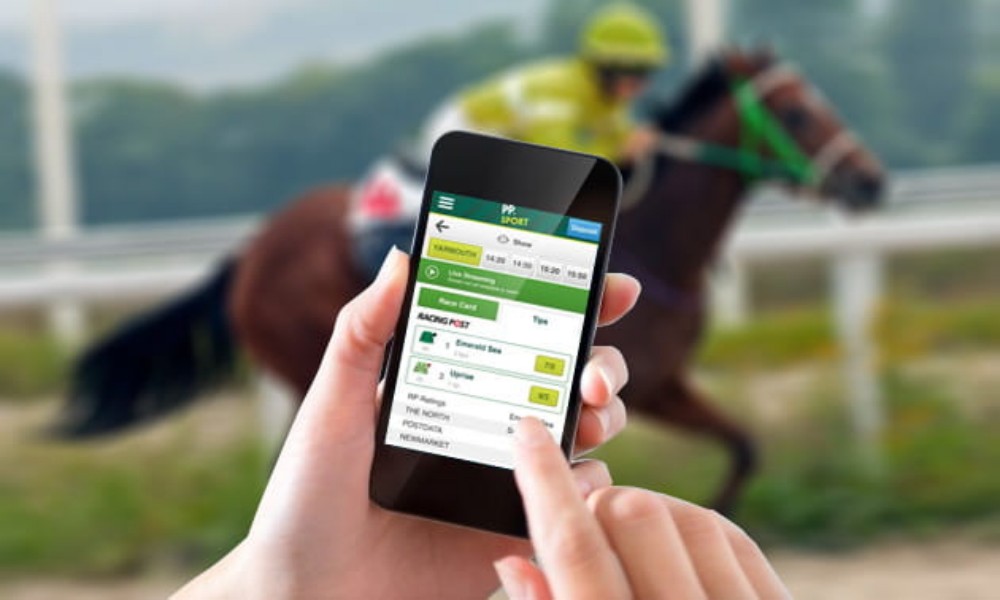

The paradox of modern horse racing is that the sport itself is declining in popularity, yet the mechanisms created around the racecourse are more powerful than ever in football, tennis, esports and dozens of other disciplines.

Perhaps racing has sacrificed its own fame to build the vast industry in which other sports now play the starring roles. As bookmakers develop new mobile apps and add fresh markets to their coupons, the silhouette of one figure is still visible in the shadows of all these innovations: the noble animal – the horse – with which the history of modern betting began.